Silicon Folklore

Was The Internet designed to survive a nuclear attack? The History of the Narrative History of the Internet

Was The Internet Designed to Survive a Nuclear Attack?

(Note: The print version has videos and some artwork removed. Hyperlinks are numbered like so [L##] with a corresponding list at the end)

You've probably heard the story of how the Internet was designed to withstand a nuclear attack. It usually goes "DARPA was doing cold war planning and was eager for a distributed resilient command-and-contro"… actually let's hear Professor Rob Larson, author of Bit Tyrants: The Political Economy of Silicon Valley, give it on Oct 18, 2022:

Apparently, the Internet is from "back in the 1980s", was called DARPAnet and was built to defend against a nuclear attack.

Is that true? Let's find out.

This is the story of the various histories of the Internet, where they came from and which ones are real.

The early Internet didn't look like the mountainside NORAD bunkers you see in movies. Instead it was computers sitting in normal offices in university buildings without any backup power, fortification, security (network or physical) and no connections to military communication. Designed for World War 3? The children in "Duck and Cover" from 1951 had a better chance of surviving.

The "Computing on Doomsday" story is disputed by people who did the actual designing of the Internet and an older network, ARPANET.1

In texts giving Internet history a serious treatment, such as the 1996 “Where Wizards Stay Up Late - The Origin of the Internet” you can search the word “nuclear” and come up with passages like:

Bob Taylor… was also on a personal mission to correct an inaccuracy of long standing. Rumors had persisted for years that the ARPANET had been built to protect national security in the face of a nuclear attack. It was a myth that had gone unchallenged long enough to become widely accepted as fact.

and:

Lately, the mainstream press had picked up the grim myth of a nuclear survival scenario and had presented it as an established truth. When TIME magazine committed the error, Taylor wrote a letter to the editor, but the magazine didn’t print it. The effort to set the record straight was like chasing the wind

Here’s Vint Cerf, one of the key architects of the Internet, in July 2022 still trying to correct things. Apparently, the "Networking for the Post-Apocalypse" story has gotten out of hand and people who were there have been trying to politely fix things in vain for decades.

It's understandable how it could spread. Military communications during Nuclear War makes a more memorable story than designing a way to remote access what would become the first massively parallel computer, the ILLIAC IV. The funding and motivation for building ARPANET was partially to get this computer, once built, to be "online" in order to justify the cost of building it. This way more scientists could use the expensive machine.2

See you glazed over that. I know it. Isn’t bringing the mainframe to the battlefield

more sexy? That’s from June 2022.

To find out where this story comes from we're going back to when hard drives were measured in megabytes and colorful floppies arrived in your mail promising you 100 free hours online.

The origin of the origin myth

That's not a typo. We're trying to find out when the folklore began; the history of this "History of the Internet".

Prior to 1991 there is no history narrative which has the nuclear origin story so let's look at what came before.3

Back then, the stories more closely resembled the one Cerf and Taylor of the ARPANET project advocate for. In April 1988 for instance, Sharon Fisher4 in Infoworld says:

The network was originally set up for universities and research organizations to exchange information efficiently.

DARPA, the organization that funded the development of ARPANET in the 1960s (The "D" was added to ARPA in 1972) has a similar story in “DARPA Technical Accomplishments”, from 1990. ARPANET is in the “Information Processing” section claiming it's part of a larger “batch-processing” to “time-sharing” revolution (more about this later). From section 20-1:

After time sharing had been demonstrated and its impact began to be widespread in the mid 1960’s, the next logical step in this program was the linking of computers and terminals by communications networks, so that computer capabilities, programs and file resources could be accessed readily and shared remotely. The mainstream of ARPANET development involved individuals and institutions in the computer research communities which were supported by the growing ARPA IPTO program.

So what happened? We're going to set our Wayback machine to 1991 to find out. But first, homework!

Common Knowledge or "Come on! Knowledge!"

Before we continue we need a headache-inducing distinction between "common knowledge or wisdom" and "general knowledge". Common knowledge is specific to a community and general knowledge is not. For instance, cultural customs are common knowledge.

This difference is important. If you meet a foreigner, you'll likely tell them about regional laws or customs. You don't need to cite anything or know the history to be correct. It's not general knowledge because you also presume the foreigner doesn't know it.

In our context, common knowledge is a statement which can be falsified and verified wherein the one who states feels an obligation to share the information but doesn't feel an obligation to falsify or verify the statement or provide a mechanism for others to do so. In more coarse language, these are facts that go uncited.

You may notice there is a requisite of commonality for common knowledge. When trying to figure out narrative histories, whether someone cites a passage or not is a forensic tool of how common they considered the knowledge. Generally speaking, presuming good intent, the more careful a narration is, the more likely we are to an early version of it. This is of course a statistical and not anecdotal statement.

Alright, good homework. You get an A+. Let's continue.

1991: Network World Vol.8-33 P65§12. It Begins.

The first instance5 of the misattribution is both a victim of how chronology works and slight journalistic error. The August 19, 1991 issue of Network World has a biography on someone who will be important in our story, Paul Baran. It’s a long passage. I snipped the relevant parts below:

… questions were being asked regarding the U.S.’s ability to survive a pre-emptive nuclear attack with enough of its military capability intact … Baran and his RAND colleagues decided to keep the packet-switching research unclassified… After delays caused by political issues, the government commissioned a public net based on Baran’s research (my note: false). In 1969, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency completed the first packet switched net, dubbed ARPANET.

This is the correct timeline, but not the correct chain of events. It’s not the last time that mistake will be made.

This passage is buried right near the end of the magazine, after the small back-of-the issue black and white ads. But this is 1991, 13 days after Tim Berners-Lee announced the WorldWideWeb. Who cares about the Internet except for a bunch of nerds and weirdos? I'm sure it will continue to be obscure and irrelevant!

Let's move on to 1992.

1992: The Inter-what?!

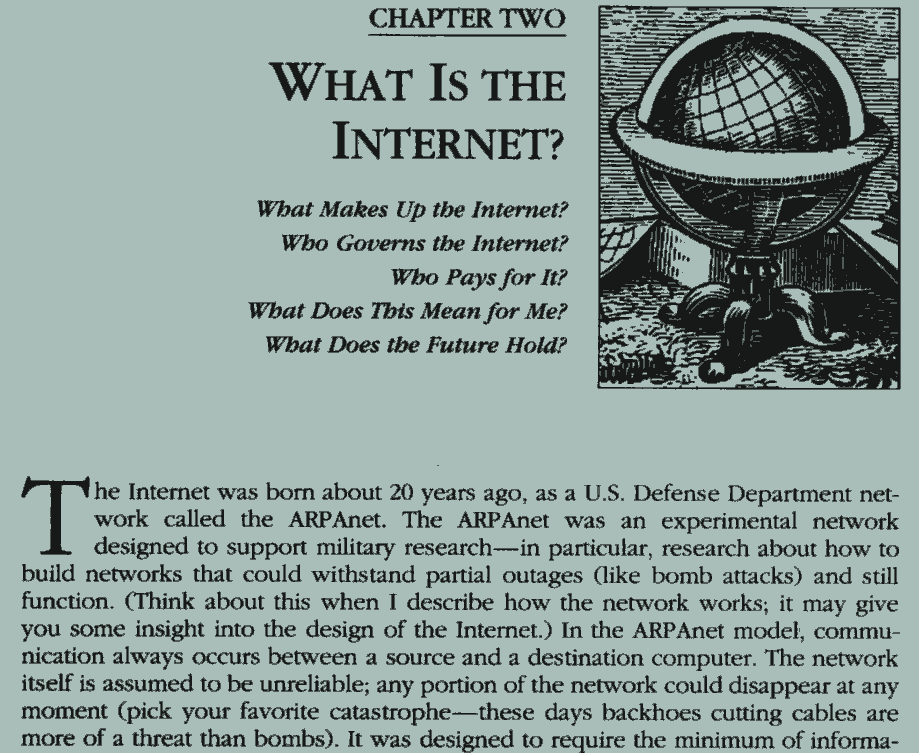

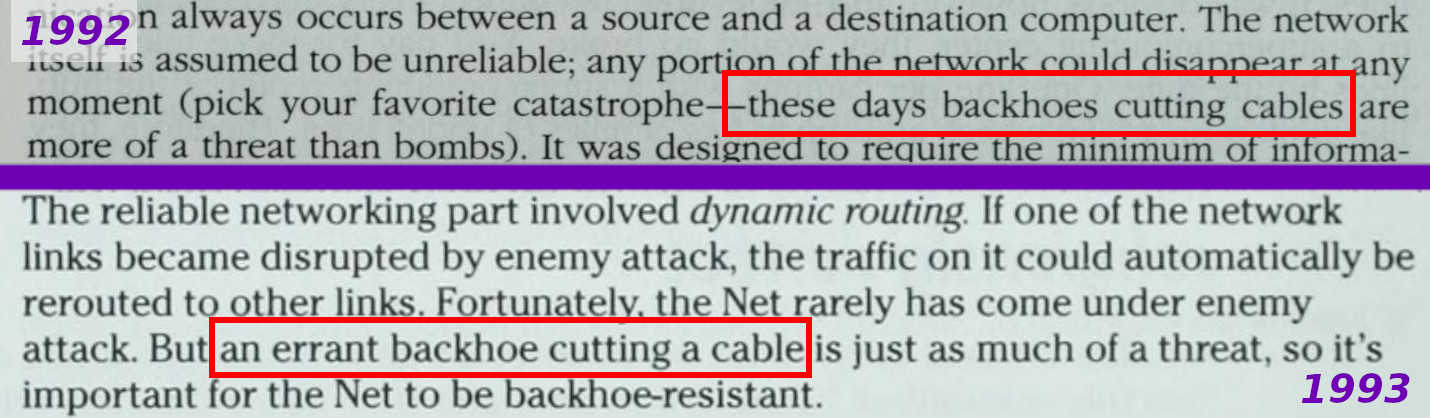

So apparently the Internet is becoming a big deal. The first prominent and more direct "Internet was designed to survive bombs" connection is in “The Whole Internet User’s Guide & Catalog” from September 1992 by Ed Krol. This is one of those books that’s so successful he came back to pen two sequels. Amazon even sells a Japanese version. Here, near the beginning of the book, we get our narrative. However, instead of “nuclear” it’s an unspecified “bomb attack”:

This is an honest error connecting a project that didn’t get approved, the bomb resilient network Paul Baran proposed to the Air Force, with the ARPA Network project (more on both of these later). Specifically this is referring to what Baran called hot-potato routing

in 1964.

Without knowing the individuals involved in each project it is understandable to assume they are connected; that a later effort was a result of an earlier effort as opposed to an independent one.

The ARPA narrative continues to persist as well such as in the 1992 “DNS and BIND in a nutshell” by Paul Albitz and Cricket Liu:

The original goal of the ARPANET was to allow government contractors to share expensive or scarce computing resources. (my note: time-sharing) From the beginning, however, users of the ARPANET also used the network for collaboration. This collaboration ranged from sharing files and software and exchanging electronic mail - to joint development and research using shared remote computers.

Looks like there's now two fairly incompatible stories. Well I'm sure this will be tidied right up. Hold on, I heard from the future. Apparently no, it's just a bigger mess.

1993: This thing's getting popular…

By 1993, second generation references start to pop up. For instance, "The Internet for Dummies", in a section written by John Levine elaborates multiple narratives including from Ed Krol's 1992 work down to oddly specific details:

(Note: John Levine responded to and disputed this section. Please see the note below for more information.)

The generic bomb gets an upgrade in what was at the time, a best-seller, the 1993 text, “The Internet Navigator” by Paul Gilster which, on page 14 says in an uncited passage:

The ARPANET was a network connecting university, military, and defense contractors; it was established to aid researchers in the process of sharing information, and not coincidentally to study how communications could be maintained in the event of nuclear attack.

Ladies and gentlemen, we’ve gone nuclear.

Also, notably, in February of 1993, the science fiction author Bruce Sterling writes perhaps the most compelling narrative fixture of what becomes a later source. This text was shared around USENET throughout 1993. USENET was in practice, social networking over email.

In it there’s a clean narrative line that’s drawn between Paul Baran and ARPANET. It’s a long passage so some cutting was done:

…the RAND Corporation, America’s foremost Cold War think-tank, faced a strange strategic problem. How could the US authorities successfully communicate after a nuclear war?

Postnuclear America would need a command-and-control network, linked from city to city, state to state, base to base. But no matter how thoroughly that network was armored or protected, its switches and wiring would always be vulnerable to the impact of atomic bombs. A nuclear attack would reduce any conceivable network to tatters. …

RAND mulled over this grim puzzle in deep military secrecy, and arrived at a daring solution. The RAND proposal (the brainchild of RAND staffer Paul Baran) was made public in 1964. In the first place, the network would have no central authority. Furthermore, it would be designed from the beginning to operate while in tatters. …

During the 60s, this intriguing concept of a decentralized, blastproof, packet-switching network was kicked around by RAND, MIT and UCLA. The National Physical Laboratory in Great Britain set up the first test network on these principles in 1968. (my note: this is the transition) Shortly afterward, the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency decided to fund a larger, more ambitious project in the USA. The nodes of the network were to be high-speed supercomputers (or what passed for supercomputers at the time). These were rare and valuable machines which were in real need of good solid networking, for the sake of national research-and-development projects.

Look how smooth that is with the phrase "Shortly afterward". He's not exactly saying they're explicitly connected, just that's the chronology. Someone misreading this as a claim of attribution probably can't be faulted.

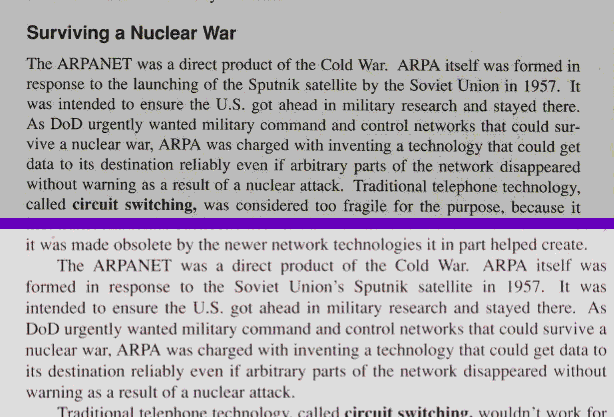

This connection can be found in other texts such as 1994’s “The Internet Connection: System Connectivity and Configuration” where the author, John Quarterman states without citation (going back to our "common knowledge" definition above) in a section titled “Surviving a Nuclear War” a very similar passage he stated in a 1993 text co-authored with Smoot Carl-Mitchell†, “Practical Internetworking with TCP/IP and Unix”:

It’s worth noting that John Quarterman might have had his mind changed on this. In an earlier, widely cited, 1990 text by him, "The Matrix: Computer Networks and Conferencing Systems Worldwide", he used a citation, suggesting we haven't entered a common knowledge phase, and told a much more ARPA history as follows:

In the beginning, ARPA…noticed that its contractors were tending to request the same resources (such as databases, powerful CPUs, and graphics facilities) and decided to develop a network among the contractors that would allow sharing such resources [Roberts 1974].

Why didn’t he stick with that?

Indeed, it looks like Quarterman had multiple tracks in his writing. For our purposes we can say there was one for a general audience and one with much more rigor (he claims this is a too primitive split see the full email dump below if interested). For instance, in the before August, 1993 more academic text with Susanne Wilhelm, "UNIX, POSIX, and Open Systems: The Open Standards Puzzle", the story given is:

…The ARPANET was created by DARPA as an experiment in and platform for research in packet switched networking.

Regardless, the "common knowledge" narrative continues to evolve.

1994: The Cathedral Becomes a Bazaar

It's 1994! Along with GeoCitites, Lycos and CDNow, we get perhaps the first claim of a direct causal connection from INSCOM (Army Intelligence & Security Command) in March 1994 on page 10:

…says University of Pennsylvania Telecommunications Professor David Farber, “that the Internet is actually a cold war relic, designed in the 1960s as a decentralized military communications system capable of surviving a nuclear attack. The Internet, which has grown explosively ever since Hurricane Andrew in 1992, has now proved its usefulness for emergency action in the civilian world.”

There's that popular phrase "capable of surviving a nuclear attack" starting up. It's a good search term if you just feel like reading a mountainful of versions of this narrative. David Farber is not a nobody. Designer of predecessor networks such as CSNET, NSFNet, and NREN, he’s a Bell Labs, SDS and RAND Corporation alumni. That last one, RAND, will be more important in our story.

We also find the older narrative “ARPANET is an indirect consequence of nuclear war planning” starting to become "common knowledge" such as in “Japan’s Information Highway” from Nov 26, 1994, also uncited:

Spawned by a Pentagon doomsday scheme to keep US military computers operating in the event of a nuclear war, the Internet…

In all these claims the statement was ARPA was looking for a resilient network due to cold war politics with the risk of nuclear war playing somewhere in the background and the ARPANET came out of this dynamic.

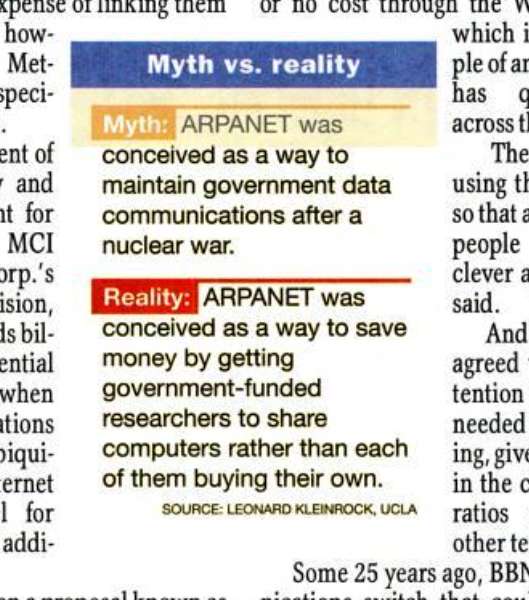

Also by 1994 the ARPA people have started to hear the nuclear narrative a bit too much. In "Network World" from Aug 22, 1994 there's “Myth vs. Reality” inset from Leonard Kleinrock in an absolutely futile effort to try and dislodge things:

It was hopeless. Network World was the first source we found for spreading it to begin with.

While we're here, the article that was referenced in "Where the Wizards Stay Up Late" from the beginning is the lead for the July 25, 1994 issue of TIME Magazine6. Here's the now common story:

The Internet evolved from a computer system built 25 years ago by the Defense Department to enable academic and military researchers to continue to do government work even if part of the network were taken out in a nuclear attack. It eventually linked universities, government facilities and corporations around the world, and they all shared the costs and technical work of running the system.

1995: The extended universe

1995! Let's log on to AOL and use the keyword MovieLink to find the screentimes for The Net with Sandra Bullock. Then we'll hop in the minivan and watch it at the mall!

By now the nuclear narrative has become "common knowledge" so people start making logical inferences from it in official documents such as the US Congressional Office of Technology Assessment's “Global Communications: Opportunities for Trade and Aid” from 1995, page 102:

…the desire for a computer network that would remain operational in the event that part of the network was destroyed by a nuclear explosion. The ARPANET therefore had no central control.

You even get hybrids combining multiple narrative strains. Watch it grow in the 1995 academic text, “Technology in The National Interest”:

war planners undertook and effort to ensure the survivability of America’s computing and communication capabilities in a nuclear first strike to preserve a credible U.S. retaliatory capability. From this initiative the first network, ARPANET, was established, allowing geographically separated researchers to share computer resources.

After that it was off to the races, such as in this 1995 text, "VRML Browsing & Building Cyberspace: The Definitive Resource for VRML Technology":

This story has serious sticking power and other than for the people who actually built the Internet, nobody seems to have any desire to correct it.

Narrative Survey

The history narrative appears to be able to be clustered in three general camps:

- ARPA: Documents bearing the ARPA name or people directly involved with the ARPANET project. (A)

- Peers: Either scholars or people who worked on other networks. (P)

- Outsiders: Those who are not in the first two groups but are what we called knowledge staters, such as reporters. They either credit members of either of the first two groups or nobody. (Ao, Po, or No). Outsiders Nobody (No) is possibly equivalent to "common knowledge".

The narrative has been broken down into a number of story points and were arranged as chronologically as possible. The methodology can be found at the end.

- Blue cells with a ✓ mean a claim was made. For instance, "Paul Baran invented packet-switching at RAND which led to ARPAnet".

- Grey cells with a § sign means things were mentioned but not causally linked. For instance, "Before ARPAnet, Paul Baran also had a packet-switching project at RAND" would be "sectional" and not "causal".

- Red cells with a ✗ mean a claim was refuted. For instance, "ARPAnet's architecture was distinct from Paul Baran's and both groups say they're unrelated".

- Empty cells mean nothing either way was said.

- Word count is the number of words dedicated to the telling of the narrative.

- The "faction" is approximately where the narrative split is (see below).

- The columns with the thicker border are ARPA faction narratives. They are additionally stylized to demonstrate a point made below.

Table headers

- 1988/04: Infoworld

- 1990/01: Matrix

- 1990/02: DARPA

- 1990/09: NYT

- 1991/08: Network World

- 1991/09: Computer Magazine

- 1992/09: Krol

- 1992/10: DNS/BIND

- 1993/02: Sterling

- 1993/09: Gilster

- 1993/11: The Internet For Dummies

- 1994/02: Quarterman

- 1994/03: INSCOM

- 1994/07: The Internet Guide for New Users

- 1994/07: Time

- 1994/08: Network World

- 1994/08: LA Times

- 1995/??: Teach yourself the Internet in a Week

- 1995/08: The Internet Show

- 1995/09: Global Communications

- 2022/02: Siliconfolklore.com

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAND/ |

✗ | § | ✓ | ✓ | § | ✗ | |||||||||||||||

| Bombs or |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | § | ||||||||||||||||

| Nuclear |

§ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | § | |||||||||

| Not Central |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | § | |||||||||||||||

| Faction | No7 | P | A | Ao | Po | No | Po?8 | No9 | Po10 | No | No | P | Po | Ao | Po11 | Ao | Ao | No | No12 | No | PoAo |

| Cost Cutting/ |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Scientific |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Collaborative |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Collaborative |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Word Count | 118 | 101 | 2050 | 316 | 200 | 136 | 60 | 86 | 683 | 110 | 168 | 91 | 24 | 388 | 228 | 42 | 520 | 53 | 9613 | 83 | 138 |

| Year | 1988 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 2022 | |||||||||||||

| Events/Era | Cold War | Gore14 | AOL Email | Netscape/Yahoo | Amazon/Ebay | ||||||||||||||||

The Winner's Circle Theory

There appears to roughly be two schools. The Peer group gave more encompassing histories then the ARPA group. The ARPA group told a history to more or less the exclusion or omission of other projects.

Because the Peer group had more moving pieces, a wider diversity of narratives could be constructed from it.

This is more a social phenomena than anything intentional and will be explored in other articles. People in "the winner's circle", defined by that which became dominant, tend to narrow the narrative and give their efforts a higher priority while the outsiders in other notable projects, tend to broaden the narrative and level things out.

They both play an important role in the documentation. The outsiders carefully document the important contributions of others while the winner's circle carefully document their own contributions. They pair together to form a complete picture.

The evidence supported story

Before we go on let's untangle things. I believe this is what has direct evidence. As this is yet an additional narrative, it's been included as the right-most column in Table 1:

- Paul Baran and RAND had a proposed network in 1965 to USAF.

- (same reference) It was not intended to use the phone system but instead, be an independent network built parallel to the electric grid.

- It was designed to be redundant, but not to scale.

- (same reference) It was meant to be used for command and control loads and not intended to be expanded beyond military communication and use.

- The 1967 ARPA Network proposal by BBN says it's for research, sharing, and cost cutting.

- (same reference) It was to run on normal phone lines and be focused on connecting nodes, presumed the network would be cared for, and did not offer extreme redundancy.

Additionally, Cerf claims the following in personal email correspondances, with verifications below:

Kleinrock did queueing theoretic analysis of capacity, delay, throughput of store-and-forward networks. The routing protocols of ARPANET were developed at Bolt, Beranek and Newman. Bob Kahn, John McQuillan and William Crowther and maybe David Walden (?) were principal architects of the routing system of the ARPANET.

Kleinrock did lots of networking work. This is a claim of the work he did specifically for ARPANET. It can be confirmed in the 1970 ARPA document, DTIC AD0711342.

BBN did its routing work independent of Davies (my note: Paul Baran believes it was based on Davies work in a 2001 Wired article) Roberts learned of the NPL work while at a 1967 ACM conference in Gatlinburg, TN. One of the NPL team, Roger Scantlebury, was there and told Roberts about the NPL packet network (Davies coined the term "packet" to describe the system he had designed). The NPL network was a single node so there was no real routing in the system. Davies did invent something he called "isarhythmic networking" but it did not scale and was not implemented as far as I am aware.

Here's the 1967 ACM Conference proceedings. There are two adjacent records in the proceedings:

- Donald W. Davies, Keith A. Bartlett, Roger A. Scantlebury, Peter T. Wilkinson:

A digital communication network for computers giving rapid response at remote terminals. - Lawrence G. Roberts:

Multiple computer networks and intercomputer communication.

Additionally Cerf backs the claim of the scaling over reliability aspect of ARPANET which really lays bare any design for nuclear survivability hypothesis:

Regarding unreliability - yes, alternative, adaptive routing was part of the ARPANET design to deal with link and/or node (packet switch) failures but the protocols internal to the ARPANET were designed to include end-to-end retransmission WITHIN THE NETWORK. The Host-Host protocol (also known as the Network Control Protocol) basically assumed the network was reliable. The Internet design, which had to cope with unreliable radio communications of the Packet Radio and Packet Satellite networks, required end-to-end retransmission at the HOST level.

Probably the most approachable narrative history of ARPA's side of the story is from a 1999 documentary, Nerds 2.0.1. The history goes from the timestamp at 19:22 to the end of the video with a bunch of interludes that make you think they're moving on from the narrative, but then they go right back. I clicked the gear, then playback speed and I know you will too.

The first article about ARPANET I could find was before it was called ARPANET. In September of 1968, Electronics Magazine:

The first time-sharing network using incompatible computers has come a big step closer to reality. The project, announced last year, now has a timetable and is ready to buy hardware, says Lawrence G. Roberts, assistant to the director of information processing at the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency. In the ARPA network, a user of one computer will have access to programs in all other machines, even if those programs won’t run on the computer to which he’s directly connected.

This was followed up two weeks later by a 4-page article. The analysis of this text is amazing. And I quote, from 1968, before the ARPANET was built:

(Distributed Denial of Service Attacks): Roberts notes that sites with smaller computers could start “ganging up” on those with larger processors. This could mean that a lot of work could be thrust upon, say, the Univac 1108’s in the network.

(Societal Implications of the Network): …geographical separation and user isolation may limit the network’s utility. Mills believes the problem may grow as the user population increases. “There should have been a definition of the relationship between a man and his program, as a unit, and the distant central machine or other data processing gear with which they are working.” In other words, Mills believes ARPA put the cart before the horse by going ahead on interconnecting computers before determining what the benefits of such a network would be.

I think this is prescient but I might be reading too much into this. Vint Cerf thinks it was impossible to predict things.2

How common are the narratives

Barry Gerber, who was contacted for this story and did some early social science research about the ARPAnet at UCLA presented an interesting question: "I have to wonder how widespread the belief in this particular myth is today".

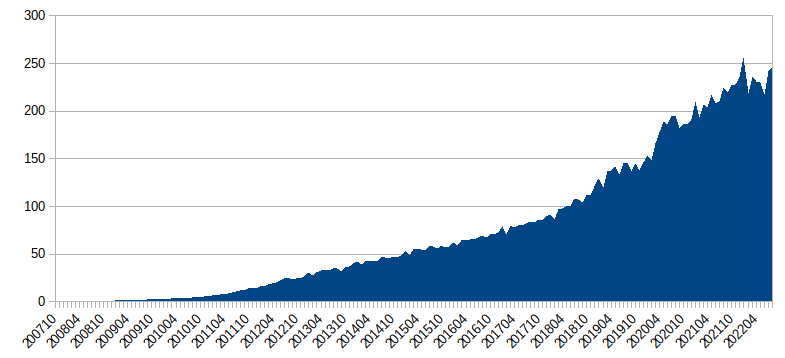

To make an attempt to discover this, a corpus of 13.5 billion Reddit comments were analyzed with a complex regex yielding 191,725 candidate comments. Then a second pass was done using a naive Regex classifier with another naive way to see if the user is negating (as in saying "arpanet was not about ww3"). No stemming, tokenizing or lemmatization was done; scikit wasn't even included. This is certainly ongoing research. (BERT Transformers are the most likely next approach along with also using the HackerNews corpus.)

The first column are affirmatives of the story point and the second columns are instances where negation appeared. The "sample size" is the total number of comments considered for a given year. You can hover over each cell to see the value on desktop.

This table does not work on the print version due to being based on cell opacity and background colors. Sorry, I'll get around to fixing this.

Notes

When filtering strictly on "ARPANET", the nuclear affirmative numbers dropped by about ~4 percentage points which is to be expected if we are to assume those familiar with ARPANET may be more likely to know the (A) narrative. To answer the posed question, it looks to be, at least according to those opining on Reddit in a way that matches my filters, about 1/6 affirm the nuclear narrative and this appears to be more or less stable over the 13 year range.

The robustness of this result is interesting. The most likely cause is my own incompetent execution. Ignoring that possibility, it's of unique interest simply because of Reddit's growth and demographic change over time.

The graph below is the month-by-month line count for the archival comments linked above. Every comment in the archives is one line of encoded JSON.

Then again, this is something that was communicated by University professors that had been publishing on networks since the 1970s. Newspapers, textbooks, congressional documents, a certain percentage all gave part of a (P) narrative. There could be more fundamental reasons for its continued persistence.

Why the Nuclear story sticks

Like good conspiracy theories, there’s related truths that make the core message believable. The ARPANET project was by DARPA, which was under the Department of Defense. This organization was launched after Sputnik. The military had something called MILNET, it’s own split-off from the Internet from 1983 which became NIPRnet.

In 1971 the command and control WWMCCS had an ARPANET like system using BBN IMPs. ALOHAnet did lead to PRNET and a packet-radio van which interacted with a satellite network, SATNET.14 Before that there was a trans-atlantic link, NORSAR connecting to seismic units in Norway to, among other things, enforce the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

There is some cold war connection, just like there is in much of computer technology from the era. The generalized statement that DARPA money funded Silicon Valley is true and it’s understandable how fuzzy memories and a bit less rigor can fuse connections.

Also there’s a conspiracy tendency when it comes to grim folklore. Perhaps people denying the nuclear war connection have a political agenda, they were misinformed or they are too scared to admit it. It has its own defense built in that permits people trying to correct the narrative to be dismissed as trying to push an opinion or occluded political agenda.

However, the documentation is voluminous and the people who were in the room have all given a consistent story about how it was to build a network for time-sharing of expensive computers and better collaboration.

People also have a tendency to not be careful with chronologies and often attribute events in a narrative structure that would require people time-traveling to be possible.

To put this in perspective let’s use living recent memory. It would be like seeing a connection between say COVID-19 pandemic outcomes being related to political governance, that there was a 2012 Ebola outbreak and then claim the outcome of the Obama/Romney 2012 election was a direct consequence of the federal COVID-19 response.

That’s really the same dynamic. Events in the 1970s are being placed categorically adjacent to events in the 1960s and after the table is set, a narrative is drawn between them.

Right Click, View Source

As I’ll cover in further articles in this series, there’s no expectation that an engineer be a historian or that accurate scholarship can be expected in the days before mass digitization especially in texts where the history isn’t a focus of the scholarship.

Also, the prevailing assumption is to look for mistakes before assuming malice. Not just because it’s more polite to do so but also because these statements are small buried passages in much larger, often dry technical works. There’s no evidence these authors are fabulists trying to tell compelling stories.

To dig deeper on this we’ll refer back to the 1990 DARPA document.

From “DARPA Technical Accomplishments”, section 20-2 we find this:

Notable early contributions had been made by P. Baran and collaborators at RAND. Baran’s work in the early 1960’s outlined a distributed, survivable digital communications system for the Air Force, in which a data stream would be broken near the point of initiation into addressed subunits of less than two hundred bits, which would then be routed by “intelligent” nodes over multiple paths which could include satellites as well as telephone communication lines. Baran’s group also ran a simplified computer simulation of such a network, using six nodes, which demonstrated its workability and survivability and indicated that the nodes did not need to store many message segments in order to be effective… A 1962 thesis by L. Kleinrock, then at Lincoln Laboratory, came to a similar conclusion.

With the important part coming after:

The Air Force did not follow up Baran’s work, apparently because of skepticism from the communications community, which felt that data hang-ups would be common and buffer storage requirements large. Baran’s work, apparently, was not well known to members of the DARPA community when they began their plans for computer communications networks.

Vint Cerf says as much in the YouTube link provided above in the first section.

The work they are referring to is entitled “Recommendation to the Air Staff” by RAND, from August 1965. Quoting page 2:

In our view it is possible to build a new large common-user communication network able to withstand heavy damage. Such a network can provide a major step forward in Air Force military communication capability.

and then page 40 for more lurid detail:

The cloud-of-doom attitude that nuclear war spells the end of the earth is slowly lifting from the minds of the many. … If war does not mean the end of the earth in a black and white manner, then it follows that we should do those things that make the shade of gray as light as possible: to plan now to minimize potential destruction and to do all those things necessary to permit the survivors of the holocaust to shuck their ashes and reconstruct the economy swiftly.

So this failed proposal in 1965 matches our claim by David Farber. They both worked at RAND. In a 2019 interview Farber stated:

It allowed me to broaden out, quite a bit…. This is also the place where Paul Baran and I became good friends. We remained so for the rest of our lives.

This is consistent. In a 1988 interview he stated similarly:

He next joined RAND Corporation in Southern California where he was “heavily involved with, and affected” by, Paul Baran’s work.

So we have two possible strains, both sourcing back to early 1960s RAND work by Paul Baran; a connection between Baran and ARPANET made by a good friend of his and an understandable scholarship mistake.

Paul Baran's side

After being rejected just to see another network take off a few years later, Paul Baran could have lived the life of Miss Havisham in contemptuous bitterness and obscurity but that’s not what he did. He dusted off his shoes, moved on and did many other great things. In March 2001, Wired interviewed him:

Wired: The myth of the Arpanet - which still persists - is that it was developed to withstand nuclear strikes. That’s wrong, isn’t it?

Baran: Yes. Bob Taylor had a couple of computer terminals speaking to different machines, and his idea was to have some way of having a terminal speak to any of them and have a network. That’s really the origin of the Arpanet. The method used to connect things together was an open issue for a time.

But some contention remained. First, as a 2016 article in The Conversation points out, RAND in Santa Monica and the original ARPANET node at UCLA were a short bus ride away from each other.

Could be a coincidence. Baran is a little skeptical of it though. Going back to the Wired article:

Wired: Taylor heard about not through you, but through Donald Davies originally?

Baran: I have two different views on that. I didn’t pay much attention to it then, but with all the nonsense about it, I went back and started digging through the old records. I don’t believe anything unless I can find it in writing, in contemporaneous documentation. I had many, many discussions with the folks at Arpa, starting in the very early ’60s. The information about packet switching was not a surprise, not new. People can listen to things and put them in the back of their mind. So you don’t know. People say they’d never heard of me at the time, yet I’d chaired a session with them in it.

Baran claims the ARPA people say they didn’t know about or were influenced by Baran’s work yet Baran finds that implausible. Vint Cerf responds to this via a personal email:

Roberts likely knew about Paul's report and had done a point-to-point experiment in 1966 (?) linking the TX-2 machine at Lincoln Labs to the ANS/Q-32 at System Development Corporation (Santa Monica spinout from RAND) using a packet-switching format.

A pont-by-point, design decision by design decision analysis could be made and it might be possible to empirically favor a single narrative but that's out of scope here. Don't worry though, it actually falls within the scope of a planned article so I should get to it eventually.

Final words

There's earlier notable history to the Internet. Vannevar Bush's "As We May Think" in July 1945 describes a mechanical microfilm archival machine he dubs the Memex. The IPTO of ARPA, JCR Licklider's April 1963, "Members and Affiliates of the Intergalactic Computer Network".

There's also many other networks long forgotten. The best reference is in the April 1972 issue of Datamation which isn't digitized yet. However, I went to the archives at UCLA and painfully montaged some photocopies. David Farber, who was mentioned above, is the author. Pages 36, 37 and 38, 39. No mention of Paul Baran or nuclear war this time in his description of ARPANET and we even got a shout out to Slotnick's ILLIAC IV which is also called out in the DARPA document, section 18-1.

Also any scholar reading this will be yelling at their computer screen right now because I seemed to have forgotten the French CYCLADES network. Disarm your keyboards, comrades, we're good.

Also, the Internet is not the ARPANET, as Quarterman pointed out in a few texts, this one from Computerworld, February 22, 1993:

The Arpanet was merely one network within the Internet. Started in 1969, Arpanet was the first distributed packet-switched com- puter network. In 1977, the Arpanet became one of the Internet’s backbone networks, and the protocol research done on the Arpanet was very influential in the development of the TCP/IP currently used on the Internet. Arpanet’s technology became obsolete, however, and it was retired in 1990.

For an exhaustive survey of 133 (yes, one hundred and thirty three) networks from 1990, refer to "!%@:: a directory of electronic mail addressing and networks" (yes, pages vi and vii were somehow included twice).

The Batch-Processing to Time-Sharing Revolution

This was alluded to above. The Internet can be seen as part of a larger movement in computing away from single monolith installations doing something called "batch-processing" to a world of "time-sharing".

At one time there was a computing center with cubby holes. You’d place your program in a cubby hole and the machine operator would eventually feed it in, generate output, and you’d come back later to see the results.

There’s all kinds of problems with this. You aren’t actually touching the computer. Syntax errors would have the turnaround time of days to correct. You had to go, physically, to the machine.

The fix was time-sharing: the ability of the computer to multi-task. This meant multiple people could interact with one computer simultaneously.

In order to do that you needed multiple input terminals. It wasn’t long before people realized it’d be nice to be able to roll their terminal home with them and just call it in.

This led to remote terminals.

Then people realized they could call up any computer once it got a phone number if only they had some agreed way to talk to it. This is still 1960s.

So you had terminals talking to computers. Surely this will be followed up by computers talking to computers. That’s an obvious next step.

ARPA even had a separate project, called project MAC, which along with having legends like Marvin Minsky and John McCarthy made a time-sharing system called CTSS.

The point is that Paul Baran wasn’t chartering a path through the wilderness. For instance, here's a 1963 text on "Communication Network … Subject to Random Failure (or Destruction)". Baran's work with hot-potato routing was a year later. Robust networked time-sharing and resource combination was the clear eventual trajectory. The obvious way to achieve this was to time-share the communication channel as well. That’s where you get packets and switching.

Or hey, there’s probably more to it. There always is.

Notes

Timeline & Thanks

I'd like to thank the following for helping put this together: Barry Gerber, Cricket Liu, John Levine, John Quarterman, Matt Campbell, Paul Albitz, Paul Gilster, Sharon Fisher and Vint Cerf.

In the spirit of full disclosure, here are all email correspondences (with personal information removed) in Berkeley mbox. Some parts refer to older drafts of the article, all of which are publicly available on github.

I was unable to find a way to reach Ed Krol or Bruce Sterling and David Farber has not responded.

Corrections and comments are welcome at info@siliconfolklore.com. You can also open up an issue on the github or even do a pull request.

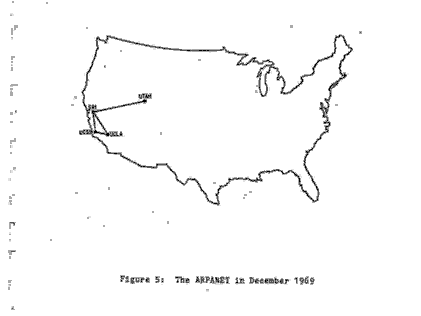

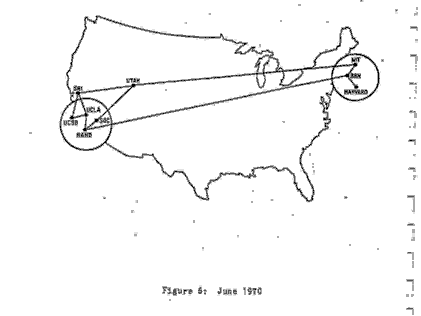

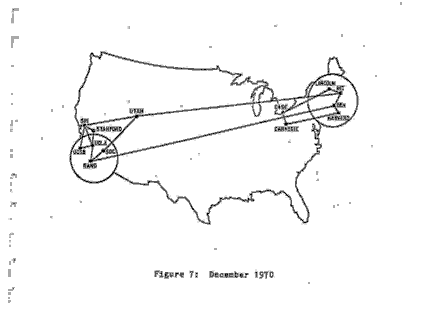

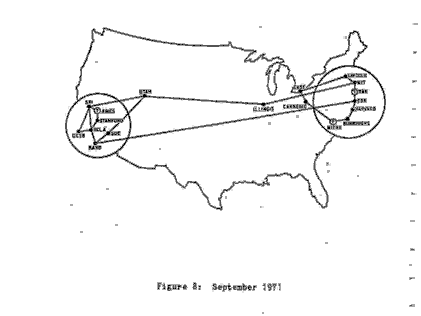

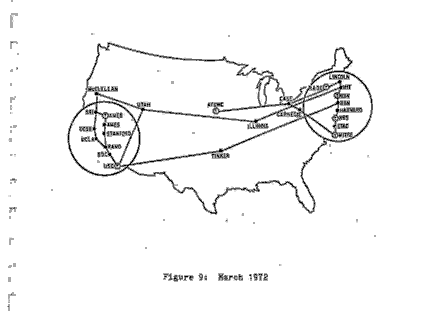

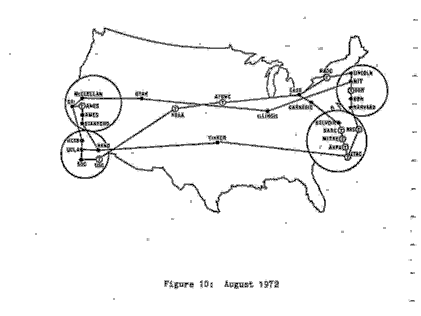

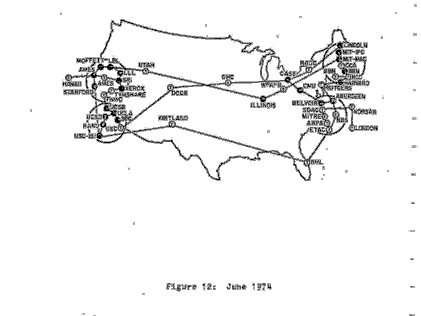

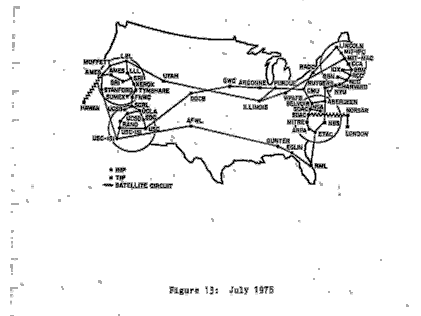

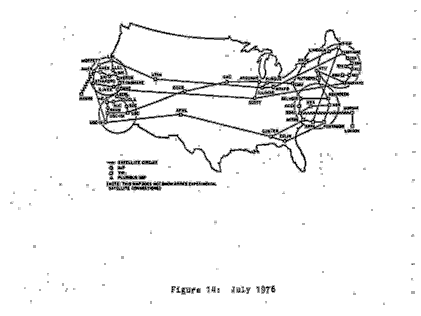

The nine colorful diagrams at the beginning forming the 3x3 motif are from the 1981 text, "A History Of ARPANet. The First Decade".

Footnotes

But not, perhaps, by ARPA IPTO (basically the CEO), JCR Licklider as John Quarterman points out in an email, linking to an excerpt from a 2017 book by Sharon Weinberger, "The Imagineers of War" (not yet available in digital libraries, excerpt from Aeon.co included) where she quotes Licklider, "Who can direct a battle when he’s got to write a program in the middle of that battle?"

Thanks to Vint Cerf for helping me on these sections.

This includes histories of the ARPANET "DARPANET" and “ARPA Network”. Please reach out if you know of any and I'll be happy to update.

Calling something "first" is so risky. Let me clarify. First as far as ProQuest, archive.org and Google books is concerned. Have an earlier one? Please send it over.

This article has been misdated on Times website. It can also be found at /time/072594/07259925.000 in the TIME Magazine Almanac CD-ROM from 1995 to confirm the 1994 date.

Quarterman's Matrix is included in Fisher's bibliography and her description mirrors the one from The Matrix. Going over the names referenced there's three without Wikipedia pages: David Wasley, David Buerger, John Rugo and Bob Metcalfe who wasn't used in the history section and is just as much a Peer as an ARPA for our imagined framework. No models are perfect.

I was unable to determine a source for Krol here. He mentions Quarterman's Matrix but that does not have the (P) bomb narrative. Krol has earlier work such as "The Hitchhikers Guide to the Internet" but nothing I could find had an origin story. He references Douglas Comer's "Internetworking TCP/IP" which is a 3-volume set also without an origin story. Comer's work references Cerf's "The History of the ARPANET" but Cerf is (A) while Krol is a (P) narrative. Also mentioned is Craig Hunt's "TCP/IP network administration" which has an origin story but it's (A) style.

An additional reference later in the work is "Computer Security Basics" which references ARPANET but has no origin story. Another reference "Practical UNIX Security" only historical reference is a brief description of Project MAC without referring to it by name.

The section from his book photographed above even gets published as RFC 1462 and here is where we find our first potential (P) link. The other author here, Ellen S Hoffman is from the alternative Merit Network which is older than the ARPANET. It plays a very important role in the history of the Internet which is outside our scope.

Also the author page of a later work from 1995, "The Whole Internet for Windows 95" claims Krol was part of the original NSFnet installation at UIUC which was part of Merit and arguably puts him in the (P) group.

These two (P) links might negate the (A) links and his direct participation does fall under the definition (albeit 15 years later so maybe not). Unless I can find a way to contact Krol, I'll have to leave that question mark there.

There's two authors listed, Paul Albitz and Cricket Liu. At first I believed the author of the passage was most likely Paul Albitz because it was repeated in "DNS on Windows NT" in 1998 and cannot be found in other work by Cricket Liu such as "DNS and BIND Cookbook" in 2003 or "Managing Internet Information Services" from 1994.

However, after effort was made to reach out to him via LinkedIn to inquire about the source, he claimed that Cricket Liu wrote that chapter. After reaching out to Liu and a few back and forth emails, his final statement is "I no longer have notes on this. I’m sorry I couldn’t find anything".

The text is not robust enough in references to lead to a factional claim, citing a few RFCs. For acknowledgments we get Ken Stone, Jerry McCollom† (HP), Peter Jeffe† (IBM), Christopher Durham, Hal Stern, Bill Wisner, Dave Curry and Jeff Okamoto. All dead-ends. Paul Albitz credits his spouse, Katherine Albitz, who is also an engineer but without any obvious ARPA or Peer connection. Further searches in google groups, proquest, and archive.org found only references to the aforementioned texts and no other works. This makes it No unless further documentation comes forth.

Sterling doesn't directly quote anyone in his February 1993 story however, in his November 1992 text, "The Hacker Crackdown: Law and Disorder on the Electronic Frontier" he talks about a 1991 CPSR roundtable mentioning two Peers:

Sixty people attended, myself included -- in this instance, not so much as a journalist as a cyberpunk author. Many of the luminaries of the field took part: Kapor and Godwin as a matter of course. Richard Civille and Marc Rotenberg of CPSR. Jerry Berman of the ACLU. John Quarterman, author of The Matrix. Steven Levy, author of Hackers. George Perry and Sandy Weiss of Prodigy Services, there to network about the civil-liberties troubles their young commercial network was experiencing. Dr. Dorothy Denning. Cliff Figallo, manager of the Well. Steve Jackson was there, having finally found his ideal target audience, and so was Craig Neidorf, "Knight Lightning" himself, with his attorney, Sheldon Zenner. Katie Hafner, science journalist, and co-author of Cyberpunk: Outlaws and Hackers on the Computer Frontier. Dave Farber, ARPAnet pioneer and fabled Internet guru. Janlori Goldman of the ACLU's Project on Privacy and Technology. John Nagle of Autodesk and the Well. Don Goldberg of the House Judiciary Committee. Tom Guidoboni, the defense attorney in the Internet Worm case. Lance Hoffman, computer-science professor at The George Washington University. Eli Noam of Columbia. And a host of others no less distinguished.

I've failed to find a way to contact Sterling to further elaborate.

Time names the following in the article: Laurence Canter, Martha Siegel, Howard Rheingold, Clifford Stoll (quoted for article, author of The Cuckoo's Egg), Steven Levy, Tom Kalil, Bruce Fancher (quoted), AJ Liebling, Adam Curry, Brad Templeton, Brock Meeks (quoted), Martin Nisenholtz (quoted), Dale Dougherty (quoted), Dave Farber, Esther Dyson (quoted) and Stacy Horn (quoted).

The documentary has a date of 1994 but an air date of 08/1995. Everything takes more than zero time to produce so we're using "release date" for the timestamping.

This is a co-production of Rice University and there's a few names I've contacted: John Levine, Gina Smith (the hosts), Bill Watts (who gets a writer credit), Kevin Brook Long (credited as "Internet Consultant"). G. Anthony Gorry (Special Thanks section, Computer Science Professor at Rice University) died in 2018. John Levine responded giving it an "Other/Nobody" or "common knowledge" mark.

- The 96-word transcript of the narrative is as follows:

Gina Smith: The predecessor of the Internet was a child of the Cold War first developed by the Defense Department's Advanced Research Projects Agency or ARPA partly to ensure the data communications could survive in case of a nuclear attack.

John Levine: Created in the late 1960s, ARPANET first connected four computers in California and Utah campuses using a new networking technique. It allowed researchers to run programs on remote computers. Later other research institutions and military sites were added. The idea was even if one part of the system were damaged, the rest would still function and it worked.

As Senator and eventual Vice Presidential candidate, Al Gore not only popularized the term "Information Superhighway" but also spearheaded legislation like the High Performance Computing Act of 1991 which funded the development of the Mosaic Browser.

The US Presidential campaign cycle of 1992 was arguably the first time (excluding the 1988/89 Morris worm) that significant effort was made to explain the concept of the Internet and (in 1993 after assuming office) demonstrate it to general audiences. See the 24:06 mark of the 1992 Stockdale Vice Presidential Debate and "Clinton to Promote High Technology, With Gore in Charge" from the November 10, 1992 New York Times as examples.

† Efforts were made to confirm these links are accurate but there has not been any response.

Backhoe Section

Here's John Levine's response to my claim of the Krol source:

The research is impressive but sometimes you just guessed wrong.

For example, the reference in Internet for Dummies about backhoe attacks didn't come from Krol's book. It was and is a cliche in the telecom world (memes hadn't been invented yet) and we both used it independently.

As a practice and a discipline, a source's claim takes precedence over any interpretation and should be disclosed. However, every subsequent claim needs to be subject to the same rigor and scrutiny and as of now, the phrasing similarity is just too close for me to claim they are disconnected. Additionally, there is no source that I could find that had such similarity prior to Krol. Of course it may not yet be digitized.

The origin of the backhoe seems to be a now obscure December 12, 1986 White Plains ARPAnet Northeast disconnect incident when 7 fiber optic cables going through the same conduit were cut. This has its own narrative history. All New England trunk lines were cut at 1:11 AM and were knocked off until about 12:11.

As far as I can tell, a backhoe started to be associated with this 1AM disconnect around 1988 and later was commonly claimed to be accidental. I was unable to find any criminal investigation, admittance of guilt, or direct evidence as to how the conduit was cut. Being an obscure event, a trip to archival rooms in New York libraries would probably be required to find out more information. Alternatively, it's possible that AT&T, which restored the line, could have a report somewhere.

I will happily annotate the section as false if more instances of backhoes or related narratives comes forward as removing it could lead to Mandela effects and further folklore.

Survey Methodology

Search queries were performed on archive.org text search, Google books, Google groups and ProQuest Central with the access covered by the LA public library card between February 18 2022 and March 6 2022.

Terms searched were "arpanet", "arpa network", "darpanet", "internet 1969", "internet history", "internet started", "internet atomic", "internet bomb", "internet nuclear", and "internet war"